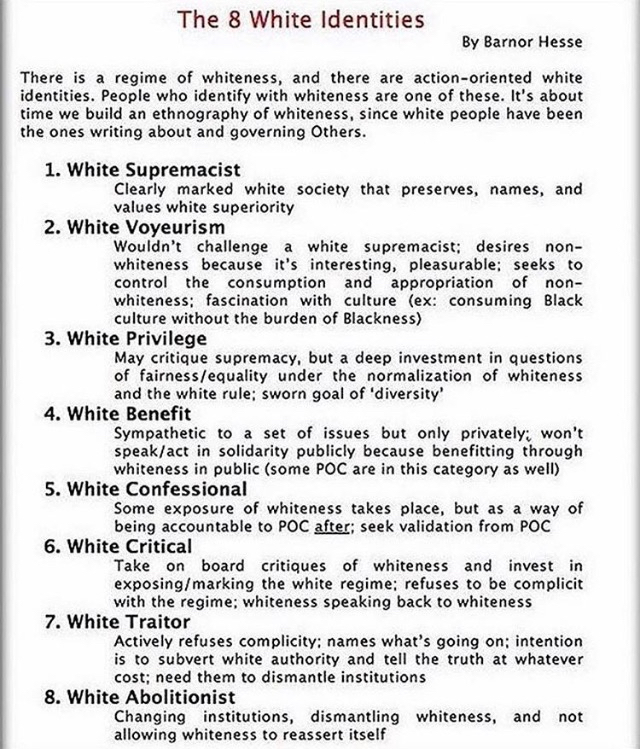

The three of us (Royona, Arabella and I) have been thinking about how our conditioning as academics constructs the way we know things; that knowing something about, for example, white supremacy is filtered by being bound to academia, and how academia expects ideas to be understood, translated and communicated.

Here’s Azeezat Johnson:

One example of these imperial histories can be seen through the distance assumed between the (majority white and middle-class) academic knower and the (majority non-white and working-class) academic known. Through this distance, the academic ‘knower’ is able to position themselves as separate and above the ‘field’ that is being studied. The academic knower ‘becomes the backdrop of nature itself, the omnipotent position of the gaze’. This objectifies those bodies that are positioned as outside the role of The Academic. This is particularly pernicious given the over-representation of white bodies within academia: there has to be a sustained critique of the way such knowledge is created through the neutrality of whiteness.

— Azeezat Johnson [1]

Such objectification is inevitably going on in this research: I am that academic knower, gazing through the neutrality of whiteness. But the objectification in my case is also complicated by the sense that when it comes to contemporary dance, I associate myself with the field or ‘tribe’ of contemporary dance. It is a collection of people to which I belong. I am on the inside, while at the same time on the outside looking in.

[1]: Johnson, A., 2018. ‘An Academic Witness: White Supremacy Within And Beyond Academia’, in: Johnson, A., Joseph-Salisbury, R., Kamunge, B. (Eds.), The Fire Now: Anti-Racist Scholarship In Times Of Explicit Racial Violence. Zed Books, London, Chapter 2 (no page number).